I had ended up at the Musée de l'Orangerie through a series of circumstances that had irrevocably altered my best laid plans for the day. I had wanted to go to the Rodin Museum, if only to live out my childhood memory of staring wistfully at “The Thinker,” but it was closed on Monday. My parents had raved about the Impressionists exhibit at Musée d'Orsay, but a few taps of my phone keyboard revealed that it was also closed on Monday. This is the peril of visiting a European city on a Monday—my first mistake.

Still, an itching desire remained and would not abate, that of wanting to be lost in something, to spend hours wandering a museum with no tie to the physical world, to feel connected to something higher, the call of being an artist. I knew these experiences could not be manufactured, but I at least wanted to conjure the correct conditions in which they might be formed. Thus, I had already bestowed on the looming experience a capital letter (Experience™)—I was already imagining how I might be affected before I had even arrived, the gears of my brain humming with the potential of a divine moment of creative inspiration. What would I feel when I beheld the delicate curvature of Monet’s waterlilies against those stark white walls?

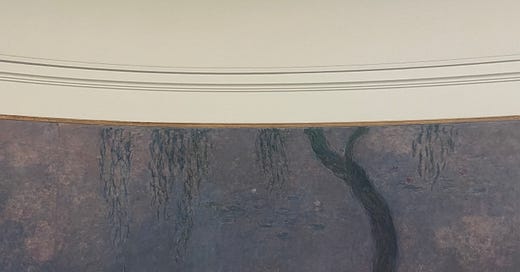

But when I finally shuffled into the illuminated museum, feeling entirely too human in my body that still managed to sweat in the July humidity, shopping bags laced so tightly around my wrist they left faint black marks, I entered the room with the anticipation of all the past museum visits before me and expected a sensation akin to awe. To describe the paintings is to do them an injustice—they are quietly stirring, they are peaceful yet dark, they are characteristic of all of Monet’s work. And yet, as I watched a young woman with her blonde hair tied in a bow turn to face the waterlilies and instruct her boyfriend to take numerous shots from behind, any budding emotion flickered and then blew out. I shifted towards the next painting, but I was beset with a crowd of young people who were all doing more or less the same thing—an angle here, a photo there, the backdrop was simply too compelling to miss.

After a few minutes of this, I resigned myself to my obvious fate, a fate that should have been obvious from the very beginning. There was no moment of enlightenment awaiting me. Whatever effect Monet might have had on me, today, it was not going to happen. Instead, my body went into a state of numbness—I couldn’t engage with the paintings on an emotional or intellectual level. I simply felt that I was looking at oil on canvas—the literal accumulation of physical parts. I roamed from room to room, hoping that the voices inside my head might expand instead of constrict, might offer a morsel of hope instead of utter desensitization, but they refused to oblige.

“The opposite of depression is not happiness, but vitality,” says writer Andrew Solomon in his 2013 TED Talk detailing his experience with the mental illness. This is, yes, an oft-quoted excerpt, but that is because it captures something quintessential about our human condition. Maybe absolute devastation of the soul is not sadness, which is still in and of itself a feeling, but numbness, which is the great abyss. Standing in front of the waterlilies and feeling completely disassociated from my body and my mind, unable, really, to feel much at all, made me wonder about the point of all this traveling we do. I didn’t want to go from place to place, to seek Experience™ after Experience™, because someone else had gone there before me, because it was part of the traditional Paris itinerary, because everyone else had loved it, and that counted for something, didn’t it? Here, I should note that there’s a just-as-insidious alternate strain of tourism, which suggests that we must always be seeking the Authentic Experience of a given country, and I would argue that that is equally as impossible—and certainly more exploitative.

But whether we seek the unexplored path or the overly-explored path, there is perhaps only one thing traveling should never provoke—a sense of apathy towards the world around us.

***

Last week, in Barcelona, protesters took to the streets of Las Ramblas in a stunning demonstration against mass tourism. Unsuspecting diners were sprayed with water guns by protesters, who marched with glaring signs that left no ambiguity: “Mass tourism kills the city” and “Tourists, go home, you are not welcome.”

And who could really blame them? More than 12 million people visited Barcelona in 2023, per Catalan News, and that generated roughly €9.6 billion in tourist spending, up almost 15% from 2019, according to the Tourism Observatory of Barcelona. These are the statistics that generally get trotted out—what brings more joy to the average person than economic development? It’s the GDP, stupid!1

But the group that organized this protest, Assemblea de Barris pel Decreixement Turístic, comes armed with some pretty explicit demands on their website. (The neighborhood assembly is affiliated with a number of European cities, including Lisbon, Madrid and Rome, although the following apply only to Barcelona.) Chief among them is reducing airport activity and infrastructure, eliminating use of residential apartments for tourist accommodation, reducing the number of cruise terminals in the Port of Barcelona and ending the public promotion of tourism.

Compared with other European cities, Barcelona has not been immobile on this topic. Not long before the protest, the city’s mayor announced that he would move to get rid of the licenses of 10,101 apartments that are currently allowed to operate as short-term rentals in the city. This was following something of a path: the city had already opted to ban short-term rentals of private rooms in residences in 2021. At the time, it was the only large European metropolis to have done so. But as tensions of overtourism and skyrocketing rental prices have encroached further and further on daily life, European countries and municipalities have acted—although there is always an argument to be made about whether it will ever be enough, whether the proverbial Pandora’s box has already been opened and can never be completely sealed. To name some efforts: France, for example, has recently passed legislation that could make short-term rentals less appealing to landlords, including ending a longtime tax loophole, while the city of Florence last year banned new short-term offerings in the historic city center.

In Barcelona, Mayor Jaume Collboni has declared this the city’s “largest problem.” What he means is not necessarily the astronomical amount of tourists, but the steadily increasing housing costs that make the search to rent or buy nearly impossible. In the last 10 years, according to The Independent, rental prices have gone up by 68% while housing prices have increased by 38 percent. From 2005 to 2020, the average cost of a monthly rental in the metro area of Barcelona went from 596 euros a month to more than 842 euros, according to data analyzed by Barcelona Metròpolis. In the city of Barcelona proper, the average monthly rental price reached almost 1,000 euros by 2020.

Overtourism comes at a cost—both to the residents who are increasingly pushed out of these cities and to the actual natural make-up of the cities themselves, if we might see cities as a living and breathing organism. A 2019 report from the UN’s tourism agency noted that, by 2030, transport-related CO2 emissions would increase 25% from 2016 levels if travel rates stayed consistent—representing roughly 5.3% of all man-made emissions. A 2011 report predicted that international tourist arrivals would hit 1.8 billion worldwide by 2030—they were already slated to reach 1 billion by 2012.

I live in Rome, one of the world’s most trafficked cities, and so I find myself daily confronted with the realities of mass tourism. I take my favorite bus to Italian school, winding its way down from the other side of the river to the Colosseo, and I pass by the hordes of tourists who walk, selfie stick in hand, the Via dei Fori Imperiali (itself a modern construct that pushed residents out). In moments like these, there is a thought that almost self-populates in my head: What is the point of travel? Are we even getting anything out of it at all?

But this has, of course, like all the world’s questions, been asked and answered before, by those on every side of this debate. Last year, philosopher—and subject of eternal controversy—Agnes Callard published “The Case Against Travel” in The New Yorker. I will excerpt from it, because I think the work speaks for itself.

“The single most important fact about tourism is this: we already know what we will be like when we return. A vacation is not like immigrating to a foreign country, or matriculating at a university, or starting a new job, or falling in love. We embark on those pursuits with the trepidation of one who enters a tunnel not knowing who she will be when she walks out. The traveller departs confident that she will come back with the same basic interests, political beliefs, and living arrangements. Travel is a boomerang. It drops you right where you started.

If you think that this doesn’t apply to you—that your own travels are magical and profound, with effects that deepen your values, expand your horizons, render you a true citizen of the globe, and so on—note that this phenomenon can’t be assessed first-personally. Pessoa, Chesterton, Percy, and Emerson were all aware that travellers tell themselves they’ve changed, but you can’t rely on introspection to detect a delusion.”

One of my favorite writers, Haley Nahman, has a nice response to this essay on her Substack, in which she discusses how a trip to Sicily was instrumental not in changing the innerworkings of her very soul but in brightening up the reality of her home life in New York.

“After returning to New York, my ordinary days had a new shine to them: Waking every morning and searching the apartment for my fluffy cat, taking a Saturday train into Manhattan with Avi and no plans, meeting friends for a picnic by the East River, looping the sizzling blocks around my apartment as I thought about what to write. I’d built up travel as this transcendent plane of existence, but the highs of my daily life weren’t so different from the highs of Sicily, if a little less densely packed and picturesque in a postcard kind of way.”

I’m not sure that I can say that I fully subscribe to either of these perspectives, although I realize that I quite squarely fall into the trap Callard references. I have watched far too many Female Solo Trip movies and books to not wander European cities in search of a “sensory experience,” thinking of myself as some sort of heroine, as the manic pixie dream girl of, if no one else’s, my own dreams. I am guilty of listening to music and putting on a nice dress and writing a novel in my head while staring longingly out at a horizon. I wrote this essay after doing those very things, didn’t I?

And yet, I find Callard’s text joyless in a certain way, devoid of any of the childlike fascination that is what the best kind of travel can inspire. I didn’t want to return from my trip to Paris a different person. I wanted to return from Paris feeling a little closer to the person I already knew myself to be. There’s an important and inherent difference there—I didn’t want to be an upgraded model. I wanted the sketch that was my personhood to be just ever so slightly more filled in. It wasn’t about expecting numbness or expecting to be moved—I would have failed by expecting anything at all. It was about not looking for the revelations and, instead, letting them find me.

***

The day before, I had been walking around the city with a new friend, exploring the graves of Père-Lachaise, stopping, quite predictably, at Oscar Wilde (I never did meet his ghost!) and Frédéric Chopin (who was harder to find through the brush). She told me about her favorite Anglophone bookstore, which takes its name from a famous William Carlos Williams poem. And as for that other famous Parisian English-language bookstore: “I can’t even go in Shakespeare and Company anymore,” she said. “There’s a line!”

And though it was the house that had fostered F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, Gertrude Stein, James Joyce, I couldn’t bring myself to make any type of pilgrimage out there. The contrarian part of me was afraid of becoming a stereotype, yes, (Literary Girl with Glasses Makes Her Way to Parisian Bookstore—Thinks She’s a Writer, Like Everyone Else in Line), but perhaps more importantly, I was afraid of encountering the numbness that was always lurking.

Yet while I lingered on the Orangerie’s bottom floor, gratified to be surrounded by Matisse and Modigliani, fewer people and fewer Instagrammable moments, I kept noting flashes of a brilliant dark blue. After the fourth glimpse, I turned to make out the letters on the white canvas tote just feet away from me. Straining to focus, I saw that there was no need for all the intrigue. Three words were embossed in large print across the bag’s bottom: “Shakespeare And Company.”

It was clear then that there was no escaping the numbness, no escaping the crowds. There was only attempting, even if somewhat futilely, to find my own way out.

In 2022, tourism made up roughly 11.6% of the country’s GDP, considered its “main productive sector,” per a Banco de España report. Spain was also the number one European country in terms of international visitors.