The darkness of Italian womanhood

What does it mean to be a woman in Italy? The question answered in brief by its women writers.

(NB: This piece was originally published in Italy Segreta, but my editors have generously said I can republish it here. Please check out their incredible women issue.)

In the hands of any other writer, Natalia Ginzburg’s short story “The Mother” could have been maudlin, a tragic tale of two young sons who lose first their father and then their young mother too early.

But from the start, we enter an atmosphere where little is spoken and tension hums just below the surface. The young mother wants freedom from the stifling environment of living with her parents. Her father berates her, “wearing his overcoat on top of his pajamas,” when she comes home in the middle of the night: “Don’t speak because I know what you are. …You run around at night like the mad bitch you are.” The truth is that the mother has a lover, Max, and really, another life. This, it turns out, is the life she wants to live, and when Max departs forever, she finds that her life shut in with her two young sons and her parents is no longer worth living.

The mother’s suicide is not the denouement of the short story—if anything, it is more of an aside. We end with the boys taking stock of the fading memory of their mother.

“They now realized that they had not loved her very much,” writes Ginzburg, translated by Paul Lewis. “Maybe she had not loved them much either, for if she had loved them she wouldn’t have taken poison. …The years passed and the boys grew up and many things happened and that face that they had never loved very much eventually vanished forever.”

I may have actually drawn a sharp gasp when I read that sentence for the first time. After all, I had grown up thinking there were certain inalienable truths: as a mother, you did not say you did not love your child; as a partner, you did not say you did not love your partner; and as a child, you most certainly did not say you did not love your parents. Maybe you expressed them in a fit of anger, in an argument, but you would certainly never write them down with a resigned seriousness.

What’s more, the Italian mamma is a culturally revered symbol, as is the relationship between mother and child—who among us does not know the term mammone? This is the country of Michelangelo’s Pietà. But Ginzburg seems to turn this on its head. It is the mother who abandons her children and the children who admit, unthinkingly, to have never really loved her.

Yet what I found so illicit about Ginzburg’s prose was exactly what attracted one of our most famous writers, Sally Rooney, who called Ginzburg’s All Our Yesterdays “a perfect novel” in a 2022 column for The Guardian.

“It was as if her writing was a very important secret that I had been waiting all my life to discover,” Rooney writes of Ginzburg. “Far more than anything I myself had ever written or even tried to write, her words seemed to express something completely true about my experience of living, and about life itself.”

Perhaps, in a way, my reaction came from the same place as Rooney’s. It wasn’t that Ginzburg’s words didn’t resonate. I wasn’t rejecting the famous opening lines of Anna Karenina, naively thinking there were only happy families. It was just that, at least implicitly, I believed not everything was meant to be acknowledged, let alone expressed. But I was beginning to understand that, in refusing to utter certain things, we close ourselves off to maybe the only concept that matters in this life: the truth.

We have perhaps one name in particular to thank for our ability to widely read Ginzburg and her contemporaries, and it is not Sally Rooney’s. No, it is the Italian woman writer that has, in many ways, defined the perception of Italian womanhood in the last decade—Elena Ferrante.

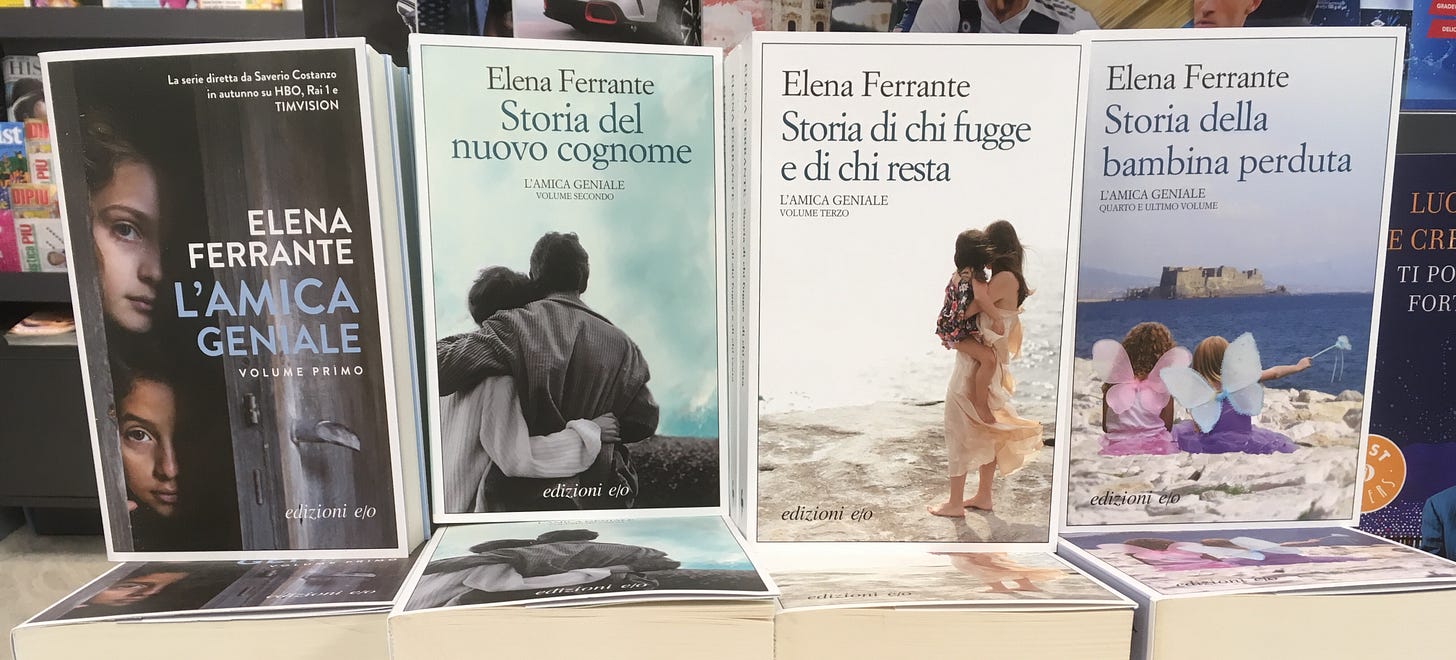

The writer’s global success may seem predestined now—there’s an oft-referenced podcast in which then-presidential candidate Hillary Clinton calls the Neapolitan novels “hypnotic.” But Ferrante’s Italian publishing house, Edizioni E/O, actually struggled to find an American publisher interested in her books in the early 2000s, so much so that they opened up the US-based Europa Editions in 2005, per BBC reporting. That decision would seem to have paid off. By 2020, the four Neapolitan novels, beginning with L’amica geniale, or My Brilliant Friend, had sold 15 million copies worldwide and been published in 45 languages.

Rooney’s characterization of Ginzburg’s work is not that far off from the effect Ferrante herself is described as having on her acolytes. Actress Maggie Gyllenhaal adapted Ferrante’s 2006 novel La figlia oscura into the 2021 film The Lost Daughter, struck in part by her intense emotional reaction while reading the book.

“I have never heard these things articulated before,” she told BBC. “There was one point where I was like, ‘This woman is so fucked up,’ and then I was like, I totally relate to her.”

To give a sense of Ferrante’s pointedness, here is a line from the very opening of L’amica geniale, in which she succinctly cuts through Rino, the son of her best friend, Lila, in just a few words.

“What a good son: a large man, forty years old, who hadn’t worked in his life, just a small-time crook and spendthrift. I could imagine how carefully he had done his searching,” Ferrante writes, translated by Ann Goldstein. “Not at all. He had no brain, and in his heart he had only himself.”

The widespread success of Ferrante’s books in the United States also opened up the market for other female Italian writers. Between 2014 and 2015, Italian-language books sold in the U.S. went up by more than 14%, according to data from La Repubblica. In June 2022, an English translation of Ginzburg’s All Our Yesterdays was reissued, with an introduction written by Rooney herself. Italian publishing company Mondadori went on to relaunch the works of another mid-20th century female Italian writer, Alba de Céspedes. Elsa Morante’s Lies and Sorcery was recently translated in English for the first time in full by Jenny McPhee. And last year, Italian fashion house Miu Miu featured De Céspedes and Sibilla Aleramo as highlighted writers in its inaugural Literary Club. Aleramo’s Una donna, published in 1906, is considered one of the first feminist Italian novels. Suffice it to say, reading female Italian writers had gone decidedly mainstream.

Still, the backlash to Ferrante fever has always been this essential question: to what extent does the rabid fascination with her work come from an American audience and not an Italian one? Georgetown University professor of contemporary Italian culture Laura Benedetti argues that it is precisely the disdain for the American public—“thought to be naive, superficial and easily falling prey to the sophisticated marketing machinations of publishing houses,” she adds, if sarcastically—that has attracted the ire of Italian critics. The 2017 documentary “Ferrante Fever” aimed to show just how the writer’s star took off in the United States, only to see a belated welcome in her home country of Italy. (She has been nominated only twice and never won Italy’s top literary prize, the Premio Strega, whereas The New York Times recently named My Brilliant Friend the best book of the 21st century.)

Anecdotally, I’ve never been able to understand how true this still is in Italy. I have Italian friends who swear by the book series, including one who was so taken with its characters that she immediately laughed at spotting a girl with a “Nino Sarratore merda” t-shirt. Yet plenty of Italians have also scowled at me when I mention Ferrante, as if I have immediately outed my own American literary sensibilities. When I told one friend I couldn’t stop watching the RAI TV series, created in partnership with HBO, he wasn’t surprised. “It’s for Americans, no?” He asked, despite the fact that the entire show alternates between Italian and Neapolitan dialect.

Even an “avid fan” interviewed by The Guardian and from the very Neapolitan neighborhood believed to be depicted in the four books noted: “I have a feeling that the phenomenon is bigger abroad than it is in Italy.”

But whichever country’s public we may say embraces her, what Ferrante has always been able to capture is the very life-or-death consequences of the patriarchy. Perhaps this is why some Italians find it so difficult to sit with Ferrante—it is too close to their lived experience. In a 2019 article for Air Mail, writer Andrea Lee summarized the complicated cultural feelings on Ferrante. She ends her piece with an anecdote of her friend’s mother, a 90-year-old born “in the Naples the author describes” and now living in London.

“My friend’s mother declared flatly that she did not like Ferrante’s work. And why was that? ‘It’s too raw,’” she said. “And by ‘raw’ she meant? ‘Real. It’s too real.’” That’s in part because the stakes often seem to be higher in Italy. More than 31% of Italian women between the ages of 16 and 70 had experienced some form of sexual or physical violence, according to 2014 data from the National Institute of Statistics. And the country has a much higher—and perhaps more visible—rate of femicide compared to the European Union. In Europe, about 29% of female victims of intentional homicide in 2017 were killed by an intimate partner. In Italy, that number was 43%, according to the European Institute for Gender Inequality. High-profile cases, like the 2023 murder of 22-year-old student Giulia Cecchettin allegedly at the hands of her ex-boyfriend, have triggered widespread protests across the country. These incidents are sadly all too common—shortly before Christmas, a 21-year-old Florentine, Martina Voce, was stabbed by her ex-boyfriend while working at a store in Oslo, Norway.

This comes in a country with a legal landscape already historically stacked against women. Less than 40 years ago, an honor killing, or murdering a “wife, daughter or sister” found engaging in an “illegitimate sexual relationship,” would have received a commuted jail sentence of three to seven years. The law was only repealed in 1981.

In some ways, an honor killing was even considered preferable to what might have been another way to deal with an infidelity—divorce. In an archival newscast reproduced on RAI, a man is asked whether he is for or against divorce, presumably before Italy granted the right to divorce in 1970.

“For example, I’m married, and if my wife were to cheat on me and we were to get divorced, I would have always been cheated on,” the man says. “So, it’s better if…” he trails off, only to make a gesture implying it would be better to kill his wife than to divorce her, to the laughs of the crowd of men around him.

And one real path to agency, that of economic autonomy, still manages to elude many Italian women. In fact, roughly 43% of Italian women between 30 and 69 were considered inactive, neither working nor looking for work, per 2021 economic data. Compare that with 32% in the European Union and only 19% in Sweden.

Despite writing roughly 80 years ago, Ginzburg and De Céspedes keenly understood the problems that faced today’s women. In a dialogue originally published in Mercurio, a monthly on politics, arts, and sciences edited by De Céspedes, the two writers debated what it means to be a woman. Ginzburg’s argument hinges on the idea that what makes women different is their “bad habit, now and then, of falling into a well, of letting themselves be gripped by a terrible melancholy and drown in it, and then floundering to get back to the surface.”

De Céspedes’ response is more encouraging, calling these wells “our strength” and noting that “it’s always men who push us into the well.”

“Because every time we fall in the well we descend to the deepest roots of our being human, and in returning to the surface we carry inside us the kinds of experiences that allow us to understand everything that men—who will never fall into the well—will never understand,” she writes. “…Because not even youth grants women the confidence that men so often possess, and that is only ignorance of the true human condition.”

This, I understood. I once got into such a piercing argument with a male friend that I felt the racing thump of my heart in my chest, a real rage—a feeling that didn’t hit me often—beginning to cloud my thinking. As he made his point with such assuredness, as if there were no scenario in which he could be wrong, a stark thought hit me: What must it be like not to hate yourself every day, not to catalogue your flaws every morning as if merely knowing them might keep you safe? What kind of freedom might that offer?

And so, I wonder if Italian writers like Ginzburg and De Céspedes and Ferrante are just a little closer to living in the spiky reality of the female psyche, a world where our warring emotional impulses might not mean that we are monsters or deranged but simply human.

This is wonderful.

It’s like if you ask Romans about “La Grande Bellezza” most of them will say they did not like the film. I refer to it as a documentary.

What a fascinating piece - thank you